Dealing with precision in AI classifiers for content moderation; inside Meta's race to catch up with OpenAI; how AI is transforming business; can someone fall in love with ChatGPT?

Gross AI kissing apps are going mainstream; most Americans use AI but dislike it; UK's plan to become an AI superpower; YouTubers sell unused footage for training data; Alexa gets a gen AI upgrade

Meta’s CEO and co-founder Mark Zuckerberg announced in a video posted on Instagram last week that the company would increase the threshold for taking down content flagged by AI-based systems, in attempt to reduce the number of mistakes that AI systems make with content moderation. When asked in a follow-up interview on the Joe Rogan podcast how the company could determine the accuracy of that threshold in practice, he said this:

Content moderation at scale remains one of the most complex challenges that technology companies have to deal with today. Having worked in public affairs roles at Meta, NetEase, and Synthesia, I’ve seen firsthand how different companies approach this challenge across different platforms, from content creation to distribution.

While the fundamentals may be the same—how to create safe and inclusive environments while respecting global diversity and giving people the ability to express themselves freely—context on how these companies operate and their business models is still important because it explains some of the decisions they’ve had to make when it comes to content moderation.

Let’s start with Meta since it is the largest social media platform in the world, with over three billion users who upload vast volumes of text, images, and videos on a daily basis. Meta’s largest app is Facebook, originally built on a social graph—a visual representation of how people, groups, and organizations are connected in a social network. The social graph began with friends and family but over time grew to include other nodes such as pages of companies or celebrities, groups of people with similar interests, or even opportunities to buy or sell products.

However, as TikTok rose in popularity, Meta moved away from relying primarily on social graphs to distribute content and embraced interest graphs, especially for Instagram. This meant that Instagram users would see less content based on the accounts they followed, and more content based on what Instagram thought they were interested in. Regardless, Meta makes money by primarily charging businesses for the ability to put ads in the front of relevant users, and thus they have an incentive to maintain a certain level of equilibrium between the experience of the users and that of the advertisers.

Given the sheer size of apps such as Facebook and Instagram, the stakes for maintaining the integrity of the platform are incredibly high: misinformation, hate speech, and harmful content can spread like wildfire at the societal level while child abuse, bullying and harassment or explicit content can cause irreparable and physical harm to individuals. The challenge is not just one of volume but also the intensity and diversity of content and cultural contexts.

NetEase is a gaming developer and publisher with hundreds of millions of players, and therefore facing a slightly different flavor of the problem. The interactive entertainment company was set up in China and expanded globally by entering into licensing deals with Activision Blizzard or Marvel. NetEase’s latest game Marvel Rivals has been a huge global hit, amassing millions of players at launch. NetEase also develops their own highly successful games in China and runs the servers for Activision Blizzard and Minecraft in that country. Games often include player-generated content such as chat messages, forums, and custom in-game assets such as skins. Content moderation here must balance the playful and often irreverent nature of gaming culture with the need to prevent harassment, cheating, and other disruptive behaviors.

More and more gaming companies have adopted a live services business model. Years ago, it used to be that you bought a game with money upfront and then you played it until you got bored, and the moved onto the next one. Now, gaming companies offer you access to the game for free but you have to pay to have a great experience, whether it’s to acquire new characters or unlock new levels. Gaming companies have an incentive to keep you in the game for as long as possible, which ultimately results in more in-app purchases.

Finally, Synthesia is a generative AI company used by over one million customers for video production. The platform allows users to create synthetic media and digital humans which, for the vast majority of people, means transforming what would’ve been an email or a plain PDF into an engaging corporate presentation delivered by an AI avatar. However, in the hands of bad faith actors, such a platform could be misused to produce non-consensual deepfakes or propagate disinformation. Therefore, unlike social media or interactive entertainment companies that handle most of the moderation at the point of distribution, Synthesia has focused on anticipating misuse scenarios by tackling these issues at the point of creation, while maintaining the platform’s creativity and accessibility.

Secondly, Synthesia is also a platform meant for business use which means it has to adopt different rules compared to consumer-facing apps or platforms. For example, many businesses do not allow employees to use profanity at work and therefore videos made with Synthesia can’t have swearing in them (which may be allowed on Facebook, Instagram or inside a game). Synthesia generates revenue by charging businesses a monthly or yearly fee to use the platform.

Content moderation is not just a technical or operational challenge; it’s a deeply human one because companies must navigate a labyrinth of global laws and regulations, societal norms, and changing preferences.

At Meta, for example, adhering to local rules in one country can clash with broader internal commitments to freedom of expression. Should a platform comply with restrictive censorship laws in one market, or take a principled stand at the cost of losing access to that market entirely? These decisions are often fraught and have far-reaching consequences.

Similarly, NetEase’s global gaming audience includes players from vastly different cultural and regulatory environments. What’s considered a lighthearted joke in one region might be offensive in another.

Synthesia’s generative AI platform adds another layer of complexity—how do you decide on content policies for an emerging technology that is still finding product fit in the market?

Nevertheless, across all three companies, AI has become the cornerstone of content moderation efforts. At Meta, classifiers scan billions of pieces of content, flagging harmful material for human review. NetEase leverages AI to monitor in-game chat for toxic behavior, while Synthesia uses advanced systems to detect content that goes against its rules before it’s generated.

The advent of GPT-class models has significantly advanced AI’s capabilities in content moderation. These models excel at understanding nuanced language, detecting subtle harmful intent, and adapting to evolving patterns of misuse. However, AI models are far from perfect. Automated systems struggle with contextual subtleties and often require human oversight to avoid overreach.

That’s why these systems don’t make black-and-white decisions when looking at a piece of content. More specifically, they don’t give a yes or no answer on whether a post or message contains hate speech or sexually explicit content or bullying. Rather, they offer a probability—a score between 0 and 100 percent—and then companies choose the level for which they consider that score to be too high to ignore. These AI models are called classifiers and the scores they produce lead to a four-quadrant grid containing:

True positives represent content or behaviors that a classifier marks as policy-breaking and which are actually policy-breaking.

True negatives represent content or behaviors that a classifier marks as not policy-breaking and which actually do not break a policy (for the record, this is usually more than 90% of what exists on the internet)

False positives represent content or behaviors that a classifier marked as policy-breaking but in reality were not.

False negatives represent content or behaviors that a classifier did not mark as policy-breaking but in reality were.

Relying on these probabilities is currently the best technical solution to allow for nuance and solve for the complexities of the grid presented above.

In an ideal world, content moderation should arrive at a state where all the potentially harmful content on a platform is found. Once that happens, the right decision is made on whether something potentially harmful is actually harmful or not (according to the content policies). Therefore, there are two intertwined metrics that underpin the performance of AI content moderation systems: precision and recall.

Precision measures the accuracy of a detection system—the proportion of correctly flagged harmful content among all flagged content. High precision reduces false positives, ensuring that benign content isn’t mistakenly removed. This is critical for maintaining user trust. Zuckerberg confusingly talks about precision in the Joe Rogan clip above but he doesn’t do a good job in my view to connect it with confidence thresholds for classifiers which are describe below. (Plus he doesn’t talk about recall.)

Recall measures the coverage of a detection system—the proportion of harmful content correctly flagged among all harmful content present. High recall minimizes false negatives, ensuring harmful content doesn’t slip through the cracks.

Basically, improving precision often comes at the cost of recall, and vice versa. For example, a system tuned for high precision might miss subtle harmful content, while one optimized for high recall might over-police and remove legitimate content.

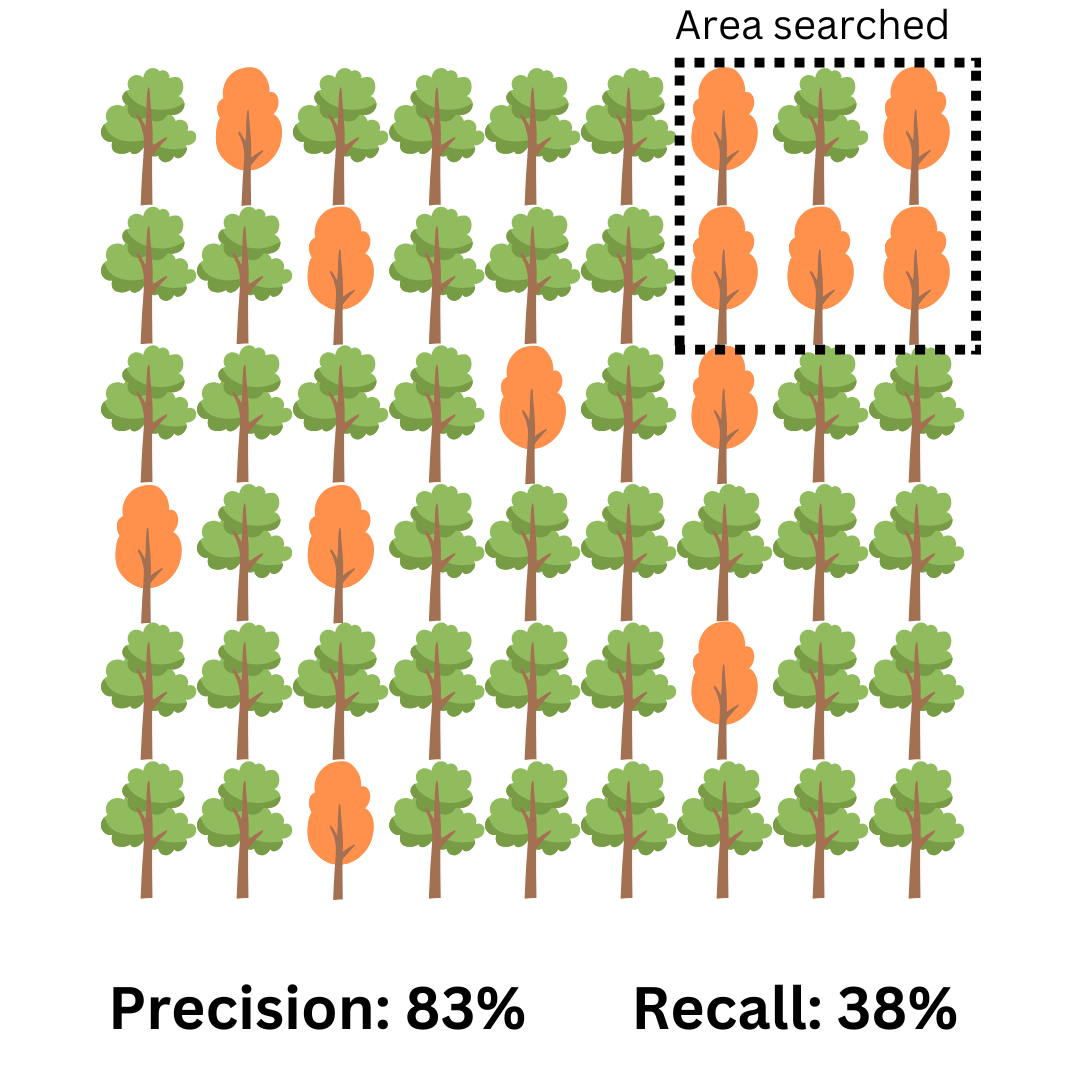

Let’s imagine you’re searching a forest, trying to find trees with brown leaves. You build an automated system to scan a picture of the forest, and it returns a set of six trees.

Upon deeper inspection, you notice that only five of them have brown leaves while one is still green. This green tree is a false positive (something the system detected as brown but was actually green). This results in a precision of 83%, which is obtained by dividing the five brown trees in the square box by six, the total number of trees inside the box. Still, that one green tree is the person whom Zuckerberg offers in the Joe Rogan podcast as the example of a user that got their Facebook account disabled by mistake which he calls “a pretty bad experience.”

Look at the rest of the forest though: by only looking at that small section, we missed a lot of other brown trees. These are false negatives, meaning our recall was only 38%, which is the number of brown trees in the box (five) divided by the total number of brown trees in the forest (thirteen). In a social network, that means for every harmful post that was taken down, there’s on average another one that Meta didn’t find.

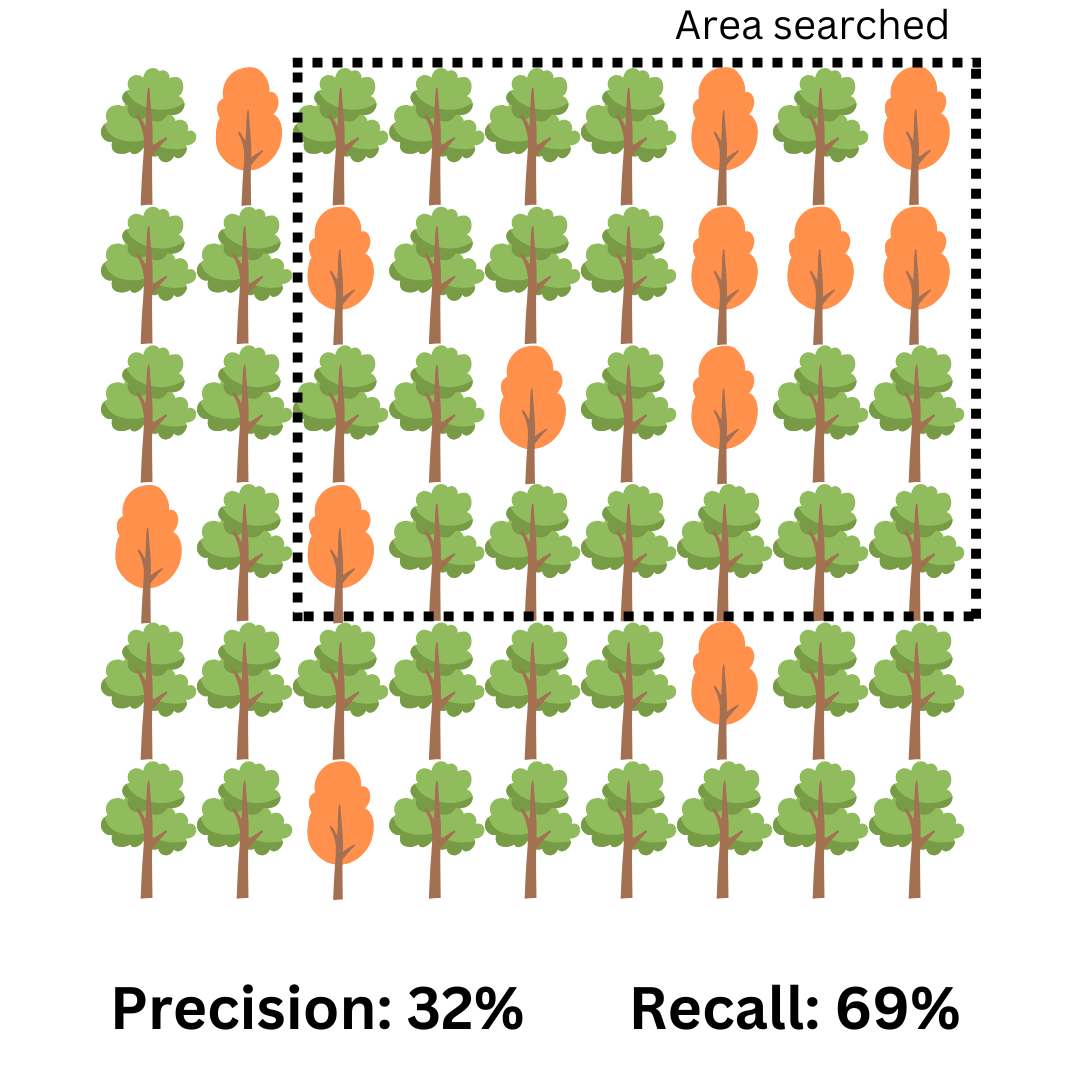

The solution to the low recall figure appears simple: let’s try and find more brown trees by expanding our detection system! Not so fast: it’s true that just by blindingly expanding the search area, we indeed find more brown trees (we almost double our recall from 38% to 69%!). However, our precision takes a nosedive, from 83% to 32%.

In practice, that means for every real harmful post taken down, the system also removes two others that were not harmful but they were mislabeled as such by the automation. Therefore, the automated system in this case is not precise enough, and valid complaints of “censorship” start to emerge.

So what can we do to address this issue? One obvious choice would be to improve these automated systems so they make fewer mistakes when distinguishing between green and brown trees.

For example, let’s take bullying and harassment in a game. If someone is repeatedly swearing in a game, are they doing so because they’re frustrated with themselves or to bully another player? Before developing these sophisticated AI systems to identify harmful content or behaviors, companies relied on user feedback or rules-based systems such as keyword detection. But these had obvious problems: keyword detection was a brute force solution which caught many false positives and allowed many false negatives. Meanwhile, putting the responsibility on the user to report harmful content allows for too many true negatives to exist.

A classifier trained on a content policy is a more elegant solution to solve for this problem. The gaming company defines a policy in plain English which describes to its players what harassment is and how it manifests in a game, and then set a threshold—say, at 70% confidence—for when to action harassment content detected by the classifier.

The harassment classifier will then be pre-trained with specific examples of players displaying harassment-type behaviors, and then will be deployed in production. Once in production, the classifier starts to analyze the language used in a chat room in real time and how players interact with each other in the game. At some point, let’s say a player becomes abusive. The classifier produces a score of 85% (which is higher than the 70% threshold) so the gaming company needs to make a choice: pass the chat logs to a human reviewer who would make a decision whether to keep the player in the game or not, or automatically ban the player from the game without any human oversight.

Now imagine making these choices billions of times a day. Striking the right balance is indeed a human choice, and depends on the platform’s goals and the nature of the content it moderates. So shifting blame on “mission creep” or “government censorship” doesn’t always tell the full story.

Finally, one more note on X and the concept of Community Notes. They may work in smaller communities and even at the societal level in countries such as Finland where digital literacy is high. But it’d be great to understand how community-based enforcement on social media will be solved in my home country of Romania where only 47.5% of students aged 16-19 have basic or above basic digital skills, 48.6% lack a minimum level of proficiency in mathematics, and 41.7% underperform in reading. If you have those levels of illiteracy in the general population, the Community Notes model immediately collapses—and the consequences are pretty stark.

And now, here are the week’s news:

❤️Computer loves

Our top news picks for the week - your essential reading from the world of AI

The Verge: Inside Meta’s race to beat OpenAI: ‘We need to learn how to build frontier and win this race’

The Guardian: Speedier drug trials and better films: how AI is transforming businesses

New York Times: She Is in Love With ChatGPT

Axios: Nearly all Americans use AI, though most dislike it, poll shows

Business Insider: Generative AI startup Synthesia just raised $180 million at a $2.1 billion valuation using this pitch deck

FT: What is Starmer’s plan to turn Britain into an AI superpower?

Bloomberg: OpenAI Emphasizes China Competition in Pitch to a New Washington

Bloomberg: YouTubers Are Selling Their Unused Video Footage to AI Companies

FT: Amazon races to transplant Alexa’s ‘brain’ with generative AI

Wired: A Spymaster Sheikh Controls a $1.5 Trillion Fortune. He Wants to Use It to Dominate AI