At NeurIPS, Europe slides further into irrelevance; behind the OpenAI-Disney deal; DeepMind signs scientific partnership with the UK; Chinese tech workers embrace Rednote; ASML faces soaring AI demand

DeepSeek is still using banned Nvidia chips; Meta's new AI talent runs into the old guard; TIME profiles the architects of AI; inside the creation of AI actress Tilly Norwood

For years, there was a comforting story that us Europeans in tech liked to tell ourselves about the transatlantic balance of power. North America had the capital and the product instincts: venture money, hyperscalers, and scrappy startups that turned research into billion-dollar businesses. Meanwhile, Europe had the brains: deep math departments at venerable universities producing a conveyor belt of top-tier researchers who would keep the continent intellectually central even if the biggest companies lived elsewhere.

In the age of AI, that story is starting to fall apart.

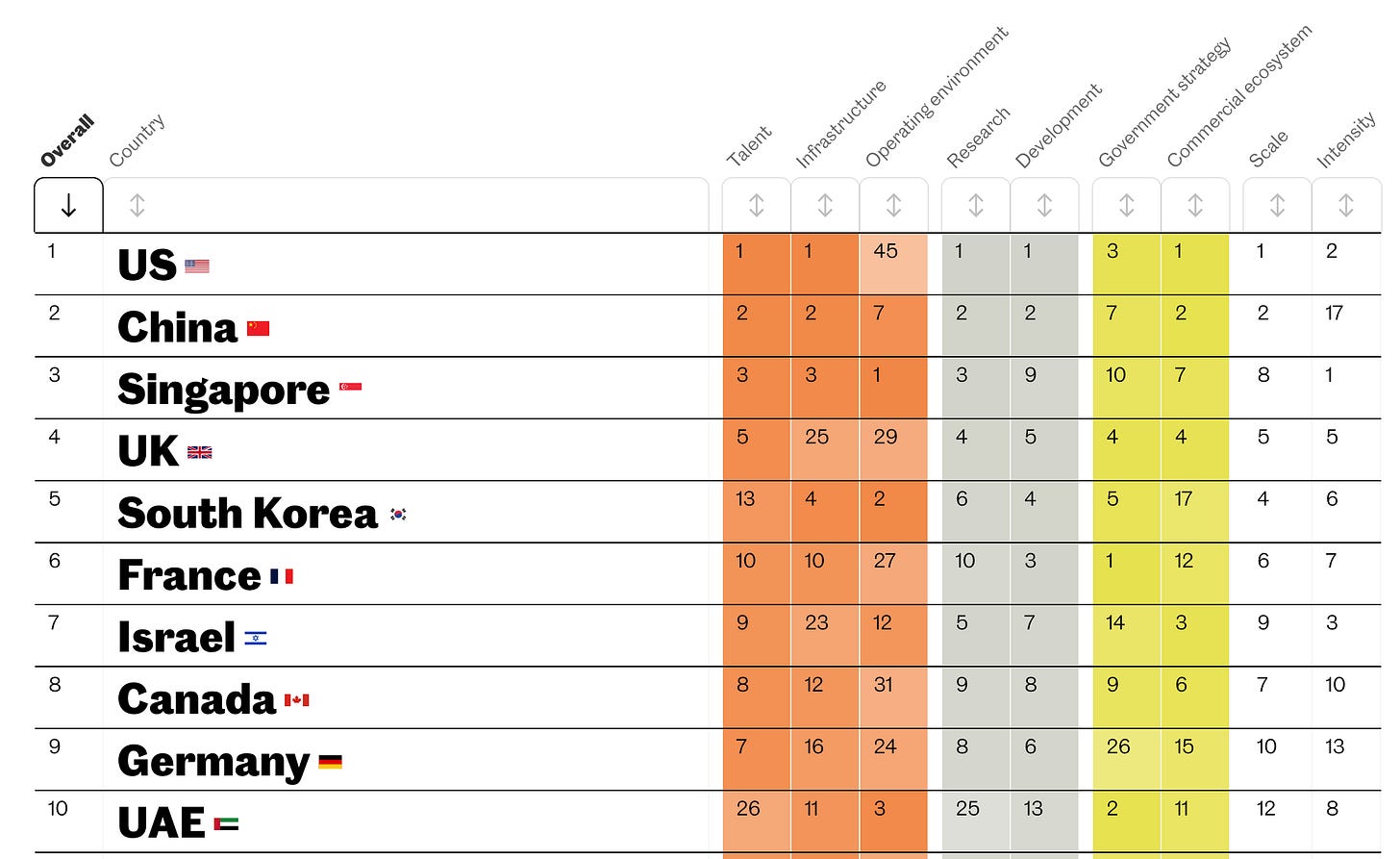

If you want to see the shift in a single snapshot, start with The Observer’s Global AI Index, a data-heavy attempt to benchmark 90-plus countries on AI investment, innovation, and adoption. Its latest edition doesn’t mince words: the US still dominates, Asian countries are rapidly rising, and Europe, despite all that talent, is falling behind. Roughly 90% of all private AI funding in the first nine months of 2025 went to the US. Europe attracted just 3.8%, and Asia 2.9%. Meanwhile, the EU’s share of papers at major AI conferences fell from 16% to 12%, and the continent is responsible for only about 13% of frontier models.

The same index highlights what’s happening elsewhere. The UAE, Taiwan and South Korea have all surged up the rankings, with the UAE jumping 10 places to enter the global top 10 on the back of massive investment in compute infrastructure and rapid AI adoption across government and society. Saudi Arabia, the UAE and others in the Gulf are now in the headlines as often for AI megaprojects as for oil.

Europe does still train world-class AI talent but it increasingly can’t keep it. The Observer’s analysis notes that the UK, for example, retains less than half of its top academic AI researchers; most move to the US. Only about 15% of top industry researchers work at UK-headquartered companies. The picture across much of the continent is similar: the labs are good, the passports are European, but the affiliation on the NeurIPS paper increasingly reads San Francisco or Seattle, not Zurich or Paris.

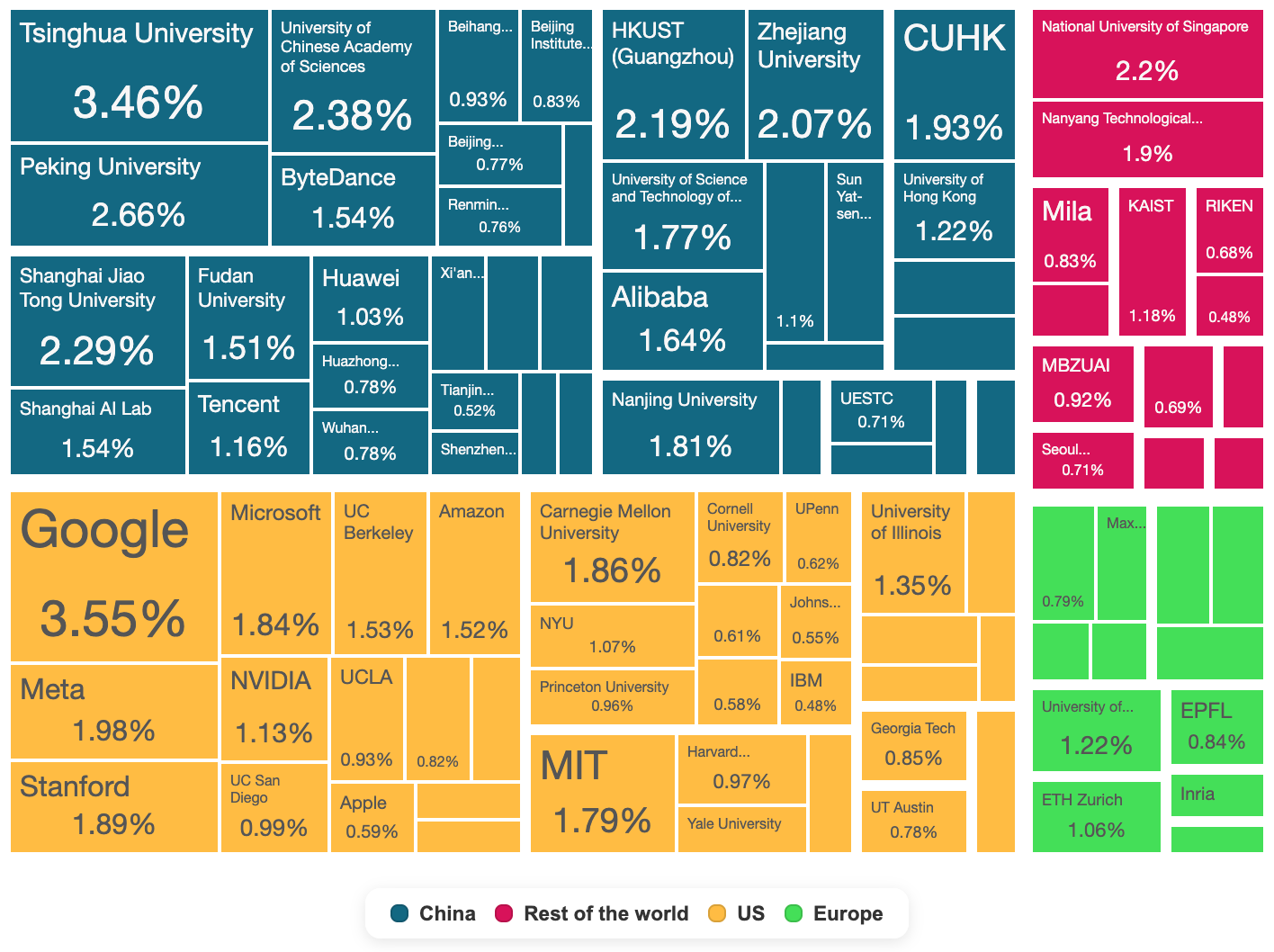

NeurIPS, the world’s flagship machine learning conference, has become a kind of global MRI scan for AI power. An analysis by AI World of the total accepted NeurIPS 2025 papers leaves little room for nostalgia. The conference, held this year in San Diego and Mexico City, is now dominated by three hubs: Beijing, Shanghai and San Francisco. Chinese and US institutions account for a substantial share of all authorships; everyone else, including Europe, is competing for the scraps.

The analysis calls out some notable institutions that sit outside the usual US–China duopoly. Among them is Mohamed bin Zayed University of Artificial Intelligence (MBZUAI), a purpose-built AI university founded in Abu Dhabi in 2019. In the NeurIPS data, MBZUAI shows up as one of the standout contributors alongside Singapore’s NUS and NTU and South Korea’s KAIST. That lines up with a broader trend: MBZUAI has already climbed into rankings of the global top 20 institutions in AI-related computer science, an extraordinary rise for a five-year-old university.

If you’re a young AI researcher, it’s hard to miss the signal this sends. Yes, conference papers are a “numbers game” in many ways: incentives favor salami-sliced work and citation cartels. But prestige conferences are still a powerful language the academic world understands. When their author affiliation maps start lighting up around Beijing, Shanghai, Abu Dhabi and the Bay Area, and dimming across big swathes of Europe, the message is clear: if you want to be at the center of the action, you may need to get on a plane.

That’s been one of Europe’s biggest blind spots: the old assumption that “we have the talent, so we’ll be fine” no longer holds. The talent is mobile. It goes where it finds compute, patient funding, and dense networks of collaborators. Right now, that’s more likely to be California, Shenzhen, or indeed the Gulf than much of the European Union. Perhaps the easiest way to understand this reality is to bring it to life with an example: while visiting Abu Dhabi this week, I was speaking with a French neuroscientist with years of experience working in industry and academia and who recently left France for the UAE to develop medical-grade brain-computer interfaces. Oftentimes, the media likes to portray moves to the Gulf as motivated purely by money, but this particular scientist had multiple successful exists, and could’ve continued to live a comfortable life in his homeland. Instead, he became frustrated with how Europe treats entrepreneurs who want to innovate, and with French regulators in particular, who kept dragging their feet over dozens of months with vague questions and unnecessary legal paperwork. In contrast, he described the regulatory approval process in the UAE as being far more intense but also fast and optimized for innovation. The Emirati regulator moved at speed to check that his project passed all their high safety standards, and then they immediately switched to “innovation mode,” connecting him with academic and commercial opportunities that matched his ambition, which would’ve never happened in Europe.

To be fair, some European leaders are not oblivious to these challenges. In November, France, Germany and the European Commission announced a new initiative aimed explicitly at “cutting-edge” AI research and digital sovereignty. Responding to this project in Le Monde, prominent figures including Max Welling and Yann LeCun made the argument that Europe does have the resources to sustain world-class AI research if it stops fragmenting them and starts acting strategically. Among the suggestions: focus on underexplored areas of the research frontier instead of chasing the biggest proprietary models, concentrate funding in a small number of agile institutes rather than thinly spreading it, and make serious, coordinated investments in compute and data infrastructure.

But there’s a tension between that vision and Europe’s day-to-day political behavior on AI. While others race to build labs and data centers, Europe has often looked more preoccupied with tinkering over the exact phrasing of AI regulation and offering symbolic support to academia that isn’t always matched by hard resources. The EU’s AI Act, for example, is still being digested by companies and universities alike; its detailed risk categories and compliance demands may be well-intentioned, but they’re also adding friction to exactly the institutions that Europe says it wants to empower. At the same time, public research budgets and national compute strategies are only now starting to catch up with the scale of today’s models.

The point isn’t that regulation is bad, or that Europe should suddenly go full techno-libertarian. It’s that the opportunity cost of political attention is real. Hours spent negotiating the 19th compromise draft of Article Whatever are hours not spent hammering out long-term funding structures or buying serious GPU clusters for European universities. In the meantime, other regions are moving faster. The Gulf states are using sovereign wealth funds to underwrite national AI champions and infrastructure at startling speed; the US continues to attract record levels of capital and talent; China has its own vast state-backed ecosystem.

Against that backdrop, the NeurIPS numbers I shared above should be a very loud wake-up call for Europe. In less than a decade, a university built from scratch in the UAE has become more visible in some AI benchmarks than many long-established European institutions that assumed their prestige was an asset no one could catch up with.

European leaders should feel uncomfortable when they look at those maps and rankings. Not because Europe has suddenly become bad at science (it hasn’t) but because the rest of the world has started treating AI as a first-order strategic priority, on a scale and with a focus that Europe has been slow to match. When 90% of private AI funding flows to the US, when Europe’s share of flagship conference papers and frontier models is sliding, and when young researchers are voting with their feet, “we have great universities” is no longer a strategy.

So what would a less complacent European response look like?

One starting point is to take the Welling/LeCun playbook seriously rather than treating it as another think-piece. That means picking a handful of locations to host truly world-class AI institutes, with guarantees of long-term funding, shared GPU super-clusters, and governance structures that make it easy for top researchers to move between academia and industry. It means aligning visa, tax and employment rules so that bringing in a brilliant PhD student from Lagos or Lahore is not a bureaucratic nightmare. It means using EU-wide mechanisms to negotiate access to large datasets in health, climate and industry, rather than leaving every project to renegotiate the same legal thicket.

It also means being honest about trade-offs. If Europe wants to be competitive in AI research, it cannot treat every GPU as a potential climate sin or every model training run as an ethical scandal in waiting. It will have to decide, in public, that some amount of risk and energy consumption is acceptable in exchange for scientific and economic leadership, and then design regulation that constrains the worst outcomes without smothering the rest.

None of this would guarantee Europe “wins” the AI race (I hate this term with a passion). The US and China are operating at a scale that will be hard to match. The Gulf is deploying capital with a speed that Brussels eggheads will never replicate. But there is still a plausible future in which Europe is not just a source of graduates and bad op-ed authors, but a place where frontier ideas are born, trained and deployed.

The alternative is to keep telling the old comforting story while the new one writes itself elsewhere: an AI world whose center of gravity runs from Beijing to San Francisco via Abu Dhabi, with Europe watching, regulating, and occasionally complaining from the sidelines.

And now, here are the week’s news:

❤️Computer loves

Our top news picks for the week - your essential reading from the world of AI

WSJ: Behind the Deal That Took Disney From AI Skeptic to OpenAI Investor

Business Insider: Meet the young AI startup founders raising millions in the race to build the next big thing

The Information: DeepSeek is Using Banned Nvidia Chips in Race to Build Next Model

The New York Times: Meta’s New A.I. Superstars Are Chafing Against the Rest of the Company

Bloomberg: How ASML’s CEO Plans to Keep Pace With Soaring AI Demand

FT: Google’s TPU chip puts OpenAI on alert and shakes Nvidia investors

Business Insider: It used to be for shopping and lipstick. Now, a Chinese app is a haven for tech workers to swap AI intel.

WSJ: Inside the Creation of Tilly Norwood, the AI Actress Freaking Out Hollywood

The Verge: AI companies want a new internet — and they think they’ve found the key

Time: The Architects of AI Are TIME’s 2025 Person of the Year